ICE Arrest of Buddhist Peace Activist Latest Evidence that US Fails to Understand Peace

Mohsen Madhawi, like Thich Nhat Hanh, finds himself in a world that requires him to take a side, and when one is forced to take a side, conflict is inevitable

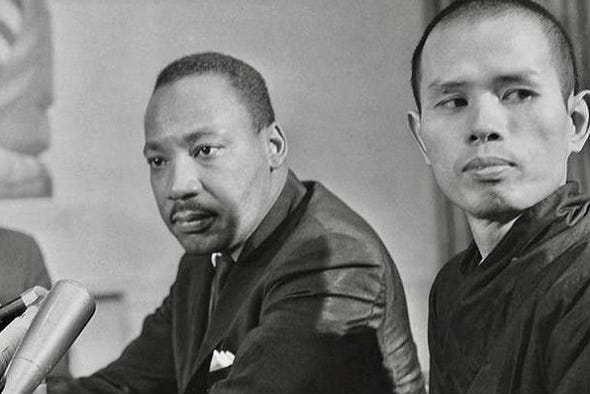

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Thich Nhat Hanh at a press conference in 1966

Last week, Mohsen Madhawi, a foreign national with legal status to be in the United States of America who resided in West Fairlee, VT, a community not far from where I live, was arrested by ICE while attending an interview that was part of the process for gaining citizenship. After being put into an unmarked van by a team of masked men he was jailed in that State pending a deportation hearing. Thanks to a temporary restraining order filed by his attorney, Mr. Madhawi is incarcerated in St. Albans VT instead of a more conservative jurisdiction — a tactic Trump’s Homeland Security office used to increase the probability of deportation in at least four other college demonstrators’ cases.

A NY Times article stated that Mr. Madhawi’s arrest was based on the legal provision that “his presence was a threat to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States.” The article described Mr. Madhawi’s campus activism as “pro-Palestinian”, noting that:

(He) co-founded Dar: the Palestinian Student Societyat Columbia University…. to “celebrate Palestinian culture, history and identity,” according to his lawyers’ petition. He also helped found Columbia University Apartheid Divest, a broader coalition that went on to lead many pro-Palestinian demonstrations on campus, pushing the university to divest from Israel.

The article went on to describe Mr. Madhawi’s decision to step back from the protests that resulted in the establishment of encampments on campus and the takeover of a campus building, citing his beliefs as a practicing Buddhist and noting that for two years he served as the president of the Columbia University Buddhist Association. The Times article concluded with these paragraphs describing Mr. Madhawi’s character and his efforts to bridge the gap between the Palestinians and Jews:

Mr. Mahdawi’s friend Mikey Baratz described him as deeply empathetic and said that, at his core, Mr. Mahdawi believed that all humans deserved to be treated with dignity. Mr. Mahdawi reached out to Mr. Baratz about six months ago because he wanted to meet Israeli students at Columbia — Mr. Baratz is Jewish and was born and raised in Israel until he left at the age of 12.

They would spend hours talking about their lives and found surprising common ground. Mr. Baratz, who graduated from Columbia in December with a master’s degree in international security policy, recently applied for a job at The New York Times.

“This is a Palestinian. I’m an Israeli. Our people are at war,” Mr. Baratz, 31, said. “And his willingness to actually hear and actively learn and understand the Israeli experience — I mean, I’ve never met anyone who so quickly was willing to take feedback.”

In effect, the United States government is viewing Mr. Madwahi’s efforts to find common ground with those who placed him in a refugee encampment when he was a child as “…a threat to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States.”

But Mohsen Madhawi is not the first Buddhist peace activist to be shunned by our country. In 1966, Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk who led a movement for peace in his country, came to the United States on a visa to lead a symposium at Cornell and several seminars in other locations under the auspices of the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam, and its U.S. unit, the Fellowship of Reconciliation. At that time, Thich Nhat Hanh’s goal was to allow the Vietnamese people to have the right to determine their own future for in 1966 his countrymen were caught in the crossfire of a proxy war. The northern part of Vietnam was controlled by communists supported by China and Russia; the southern part was controlled by a government led by Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, who was supported by the United States following his takeover of the government through a military coup in 1964. In this situation, the Vietnamese populous was divided and had no voice in determining their future.

An essay in the New York Post written during Thich Nhat Hanh’s visit to the US described him as “devoutly anti-communist as well as anti-Ky” and during his visit he met with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr who hailed him as “an apostle of peace and nonviolence". Later that year, King nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize, writing “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity"

But Thich Nhat Hanh’s pacifism was incompatible with the zeitgeist of 1966. The North Vietnamese and the American press saw him as “pro-Communist” and the North Vietnamese reviled him because of his Buddhism. As a result he was exiled by both North and South Vietnam and when the United States refused to extend his visa he sought and was granted refuge in France.

Like Thich Nhat Hanh, Mr. Madwadi is not choosing a side in the conflict between Israel and Hamas. He is seeking a voice for his countrymen, the Palestinians who, like the Vietnamese of Thich Nhat Hanh’s era, are caught in proxy war. Madwadi’s desire to find a peaceful way forward, a desire rooted in his Buddhist beliefs, hardly seems like “…a threat to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States.”

In a country that is increasingly characterized as divided, peacemakers should be welcomed. But the reporting on Mr. Madwadi illustrate the uphill battle peace activists face, for they are defined not by the middle ground they are seeking but by the “side” they are not taking. In a dualistic framework, conflict is inevitable and peace is impossible. Today, as in 1966, the problems facing our nation are seldom dualistic. They are complicated and knotty, a fact that peacemakers like Mohsen Madwadi recognize, a fact that leads them to seek the understanding of those who do not share their perspective. If, in 2025, finding common ground is “…a threat to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States” we have not learned from our experiences 60 years ago when we ignored those who sought to find a peaceful way forward in Vietnam.